How a museum in the centre of Stoke Mandeville Stadium, is dedicated to exhibiting the story of the games in a way that is accessible to all.

Many people know the story of the Olympic games, or if they don’t know the history at least know it originated in Greece. However, many don’t know and are surprised that the Paralympic games were born and bred right here in the UK, in Stoke Mandeville, Buckinghamshire.

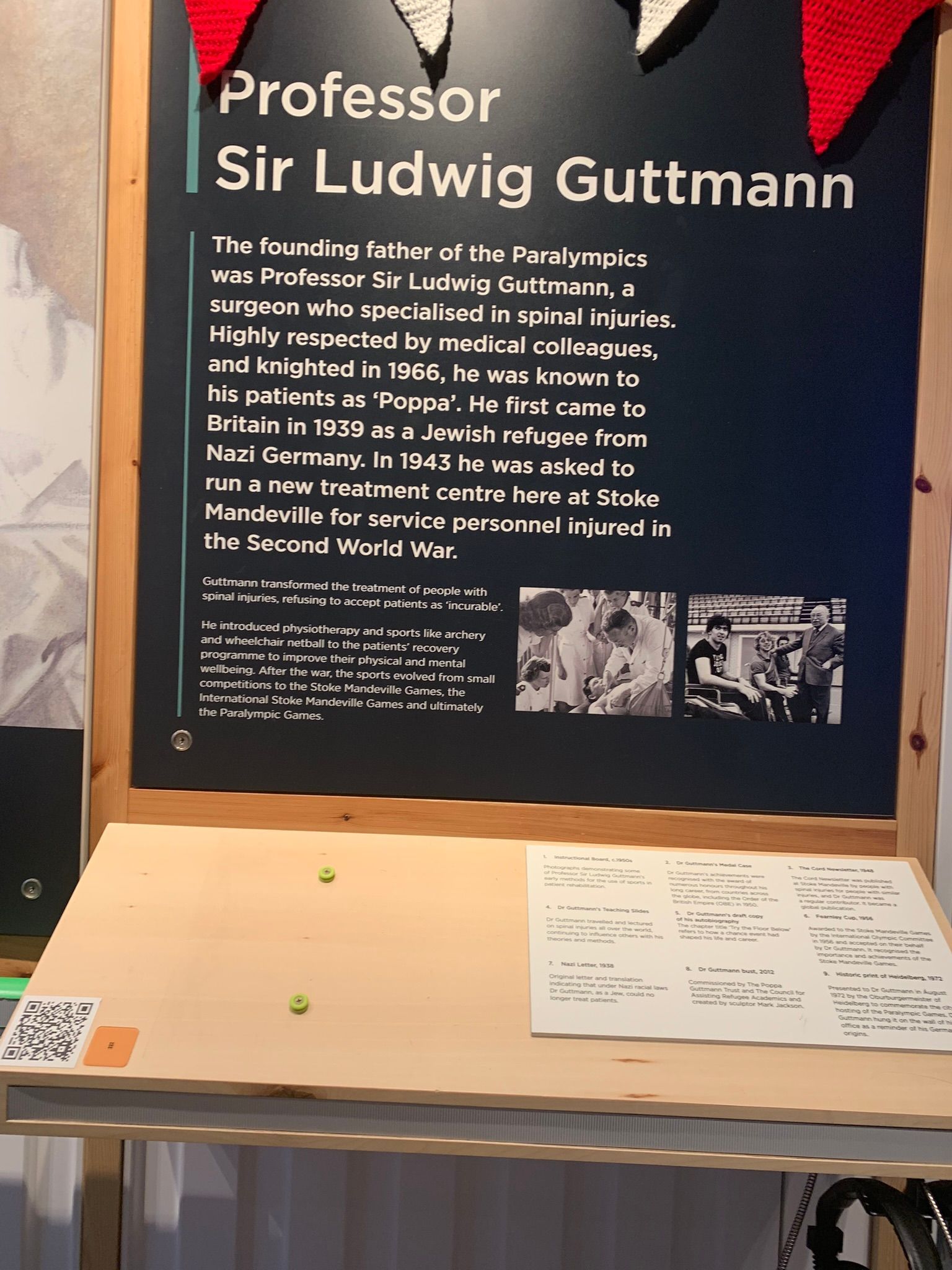

The man behind the games.

Sir Ludwig Guttmann was a Jewish refugee who fled Nazi Germany in 1939 and settled in Oxford.

Guttman was a surgeon who specialised in spinal injuries and was asked to run a new centre at Stoke Mandeville in 1943 to help injured service personnel. The National Spinal Injuries Centre opened on the 1st of February 1944, in time to help those injured in the D-Day bombings.

At the time, people with spinal injuries were given a year to live at the most, but Guttman had ideas that many did not believe in.

Many patients died due to sepsis from not moving in bed, Guttman’s idea was to take patients off sedation medication and to move the patients every two hours to stop them from getting bed sores.

He believed that using sports, helped the patients with their rehabilitation and building back their self-respect.

Patients with spinal injuries went from having a death sentence handed to them, to being given a second chance at life.

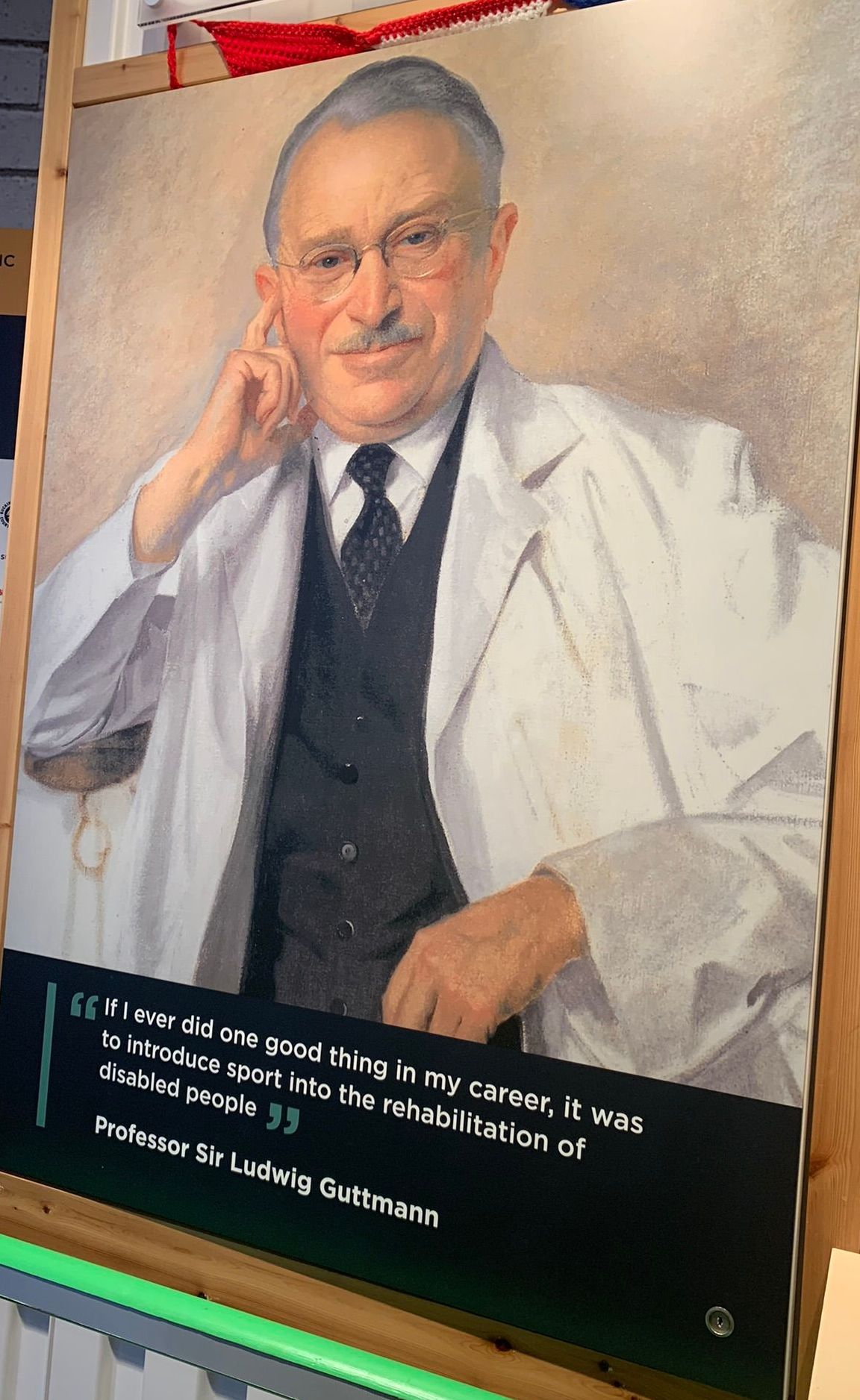

Ludwig Guttman Portrait with his famous

saying which is quoted thorughout the stadium

‘If I ever did one good thing in my medical career

it was to introduce sports into the rehabilitation of disabled people’.

Nonetheless, that day saw the birth of 16 Paralympians.

Every year Guttman, or Poppa as he was known, organised an event that grew bigger and bigger, and by 1952 Stoke Mandeville was host to a small Dutch team in their first international event.

By 1956, word had gotten out about these great games taking part in England for people with spinal injuries, and the games took shape with the arrival of countries including the USA, Australia, South Africa, and Pakistan.

Plaque commemorating the opening of the

Stoke Mandeville Stadium by Her Majesty the Queen,

1960 saw history in the making with the ‘Stoke Mandeville games’ taking place in Rome after the Olympic games. 400 athletes took part in the sport, from 18 countries. Great Britain took home 20 gold medals from the event. These were widely believed to be the first Paralympic games.

The meaning behind the name ‘Paralympics’ was not about the athletes being paralyzed or paraplegics, but refers to the word parallel, as the games run alongside or next to the Olympic games.

Until the games in 1960 only wheelchair users had been allowed to take part and no mention of disabled people with other impairments were mentioned for the Paralympics. However, in 1964 the creation of the International Sports Organisation for the Disabled started offering opportunities for those who did not conform to the requirements set out by the Stoke Mandeville Games, such as those who were visually impaired, paraplegics, amputees, and those with cerebral palsy.

The Toronto Olympics of 1976 saw visually impaired, and amputees take part in events for the first time.

The 1980 Paralympics in Arnhem, saw all four impairments represented at the games, which led to the formation of the International Paralympic Committee in 1989.

1984 saw a backward slide when New York advised they were unable to accommodate games for those with spinal injuries. Not wanting anyone to miss out, the Paralympics became a game of two cities. Those with Visual Impairments, Amputees, and Cerebral palsy would compete in New York, and those with spinal injuries and related impairments competed at Stoke Mandeville.

The games saw the flame lit at Stoke Mandeville in a cauldron, which is still in situ today.

From 1988 the Paralympic games were viewed with new ambition. Performing to sell-out crowds, momentum from here onwards built. The degree of professionalism of athletes and standards grew.

2012 saw the Paralympics come home to London. The IPC recognised Stoke Mandeville as the birthplace of the Paralympics as the flame left Stoke Mandeville Stadium at the start of the Relay.

The Paris 2024 Paralympics is said to be taking another step towards accessibility. The recent Olympic closing ceremony saw the effort they are putting into the Paralympics, with mentions of making kerbs wheelchair-friendly and trying to make the games accessible not only for the athletes taking part but also for the spectators and the media waiting in the wings.

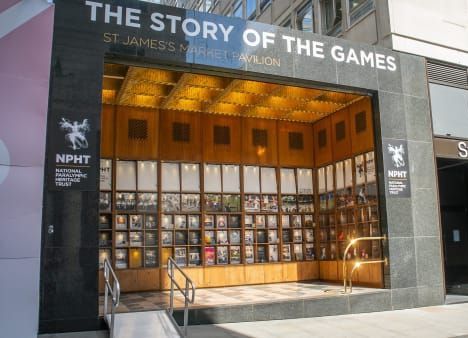

Entrance to the NPHT centre in Stoke Mandeville Standium

Picture Credit to: NPHT

The centre is home to both the story of the Paralympics but also home to many artifacts.

Being shown around the centre by Ben Banyard-Phelps, Operations Officer, was a great experience and one I would recommend.

The dedication that goes into the centre and to the online facilities by the team is outstanding.

The centre is smaller than I thought it would be, but this is a good thing if you have mobility needs or cannot take large open spaces.

Upon walking into the entrance of the museum, you are greeted by an interactive screen. What I found incredible is the detail of accessibility the team has thought of. In front of the screen is a sign in braille for those with sight impairments. The interactive screen also has an audio description.

The information leaflets, describing what is in the centre are available as both an easy read and again in braille.

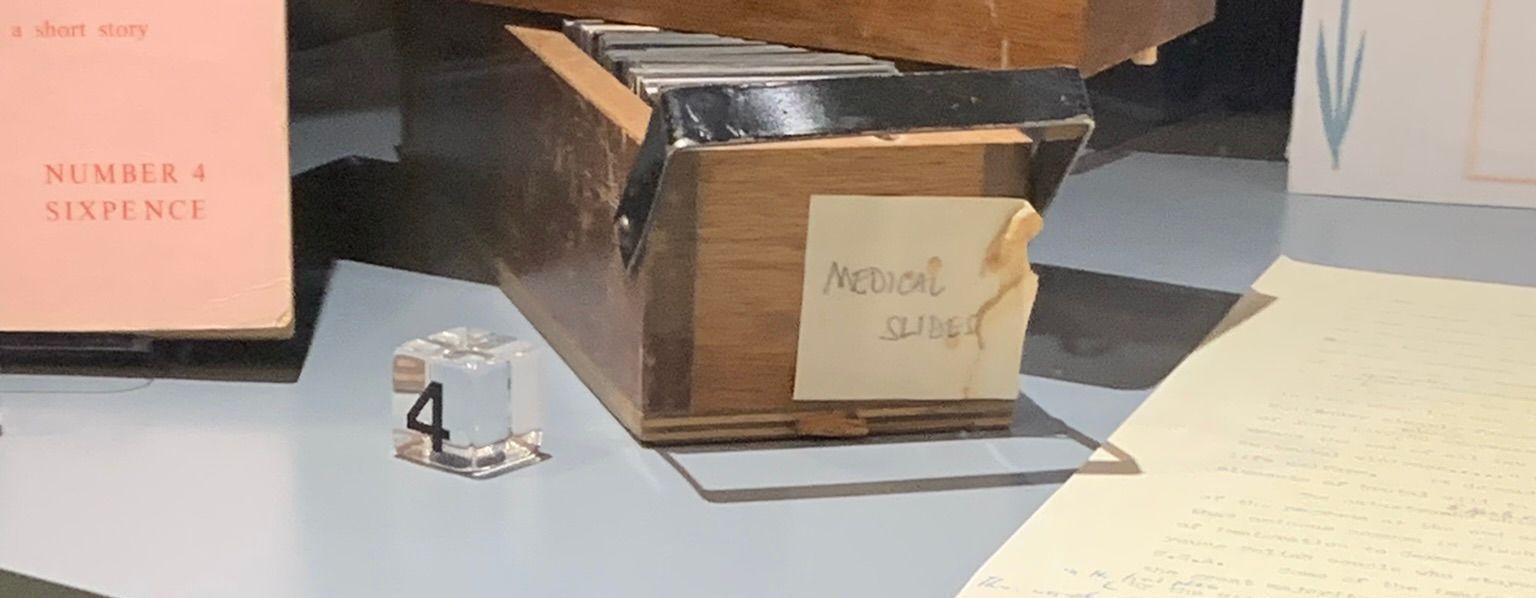

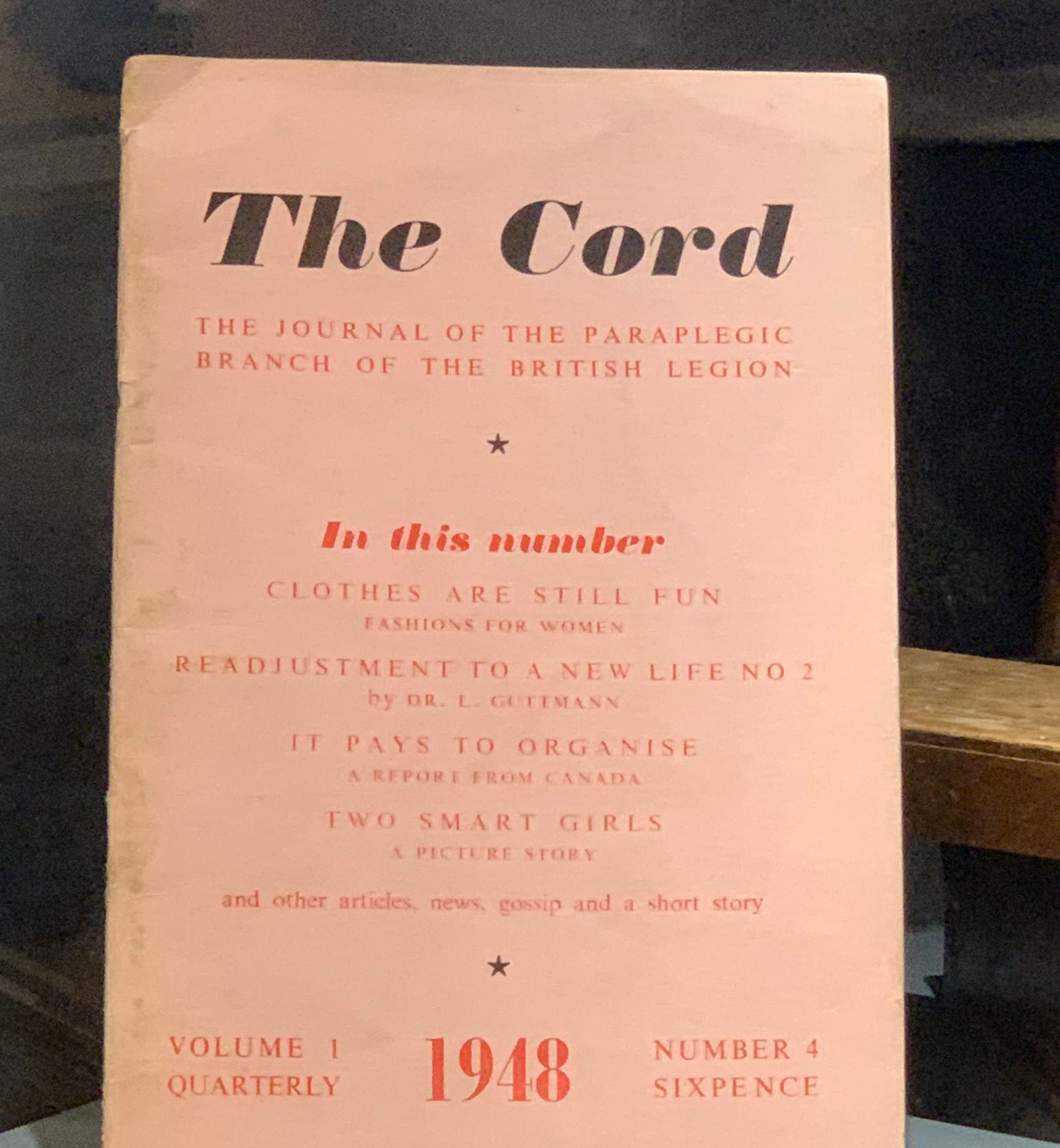

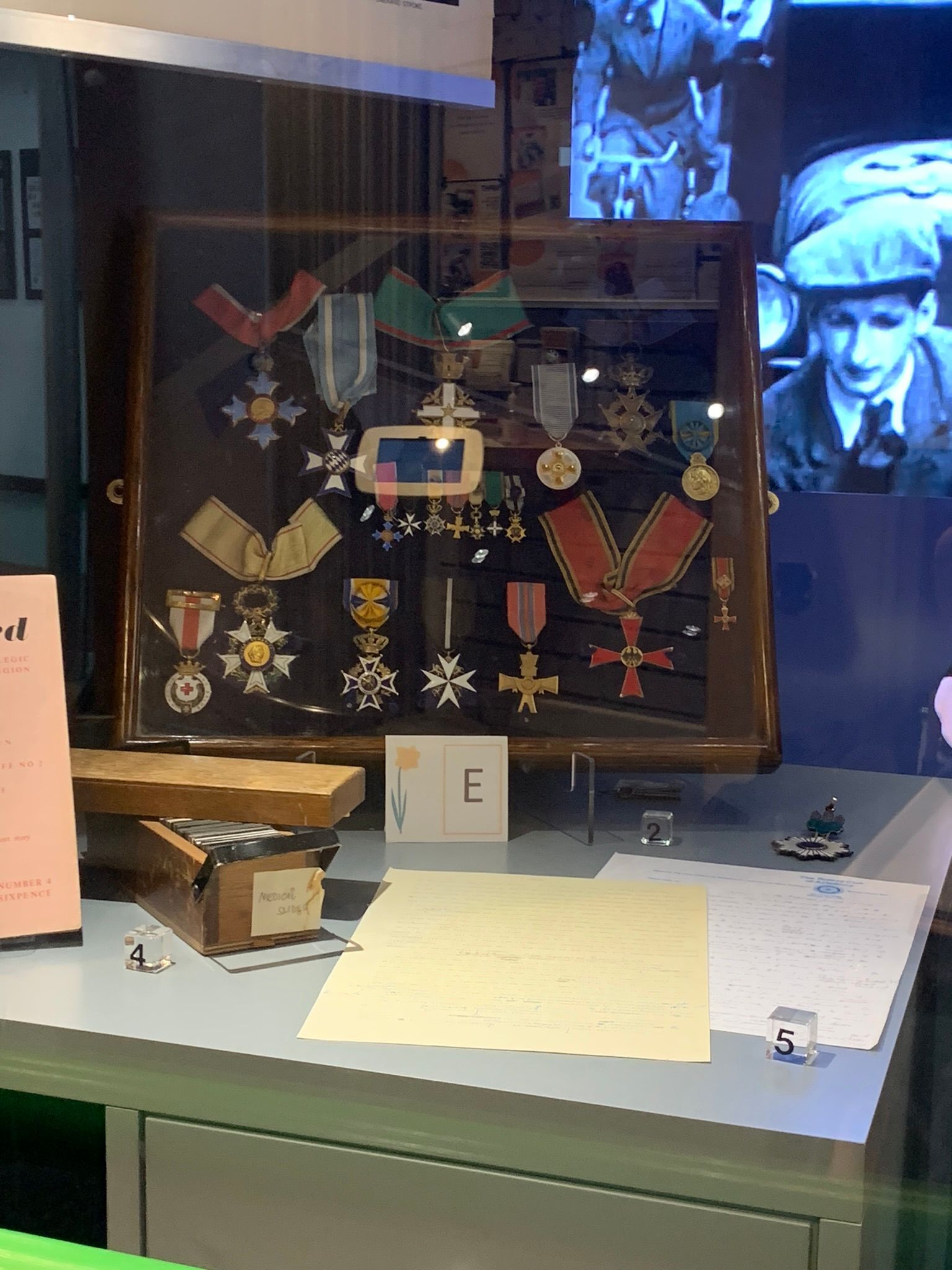

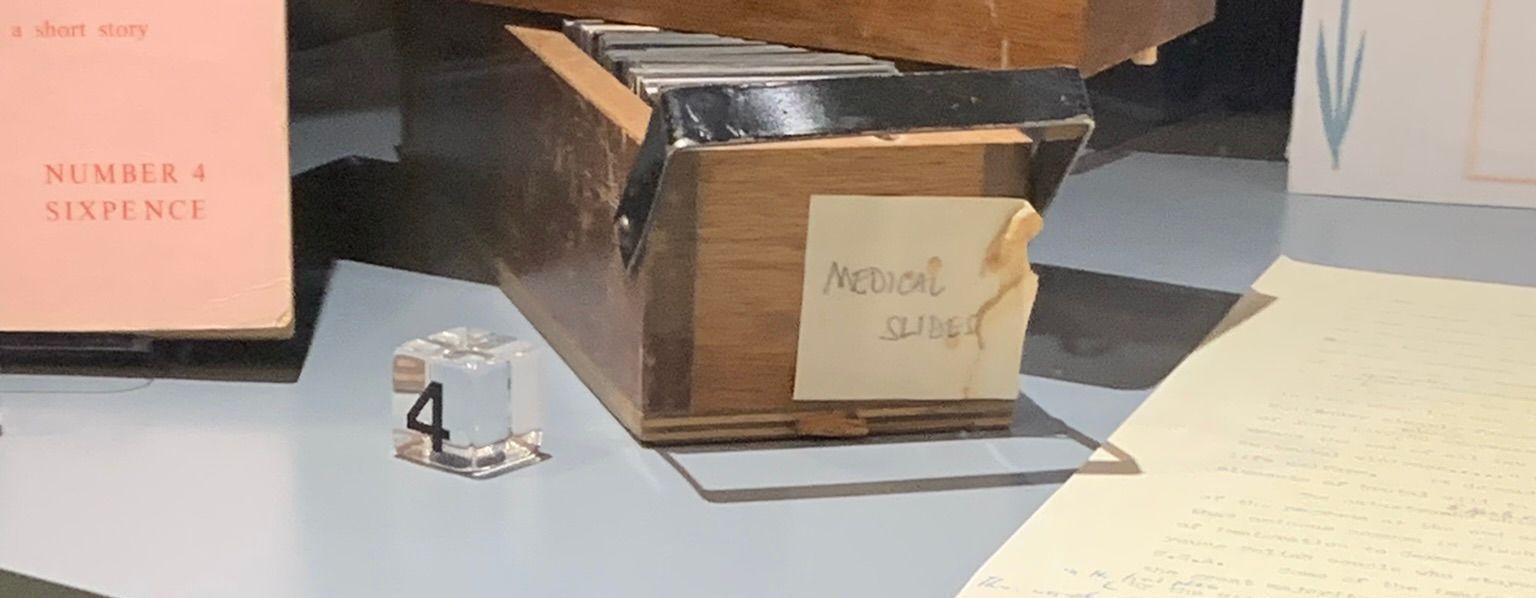

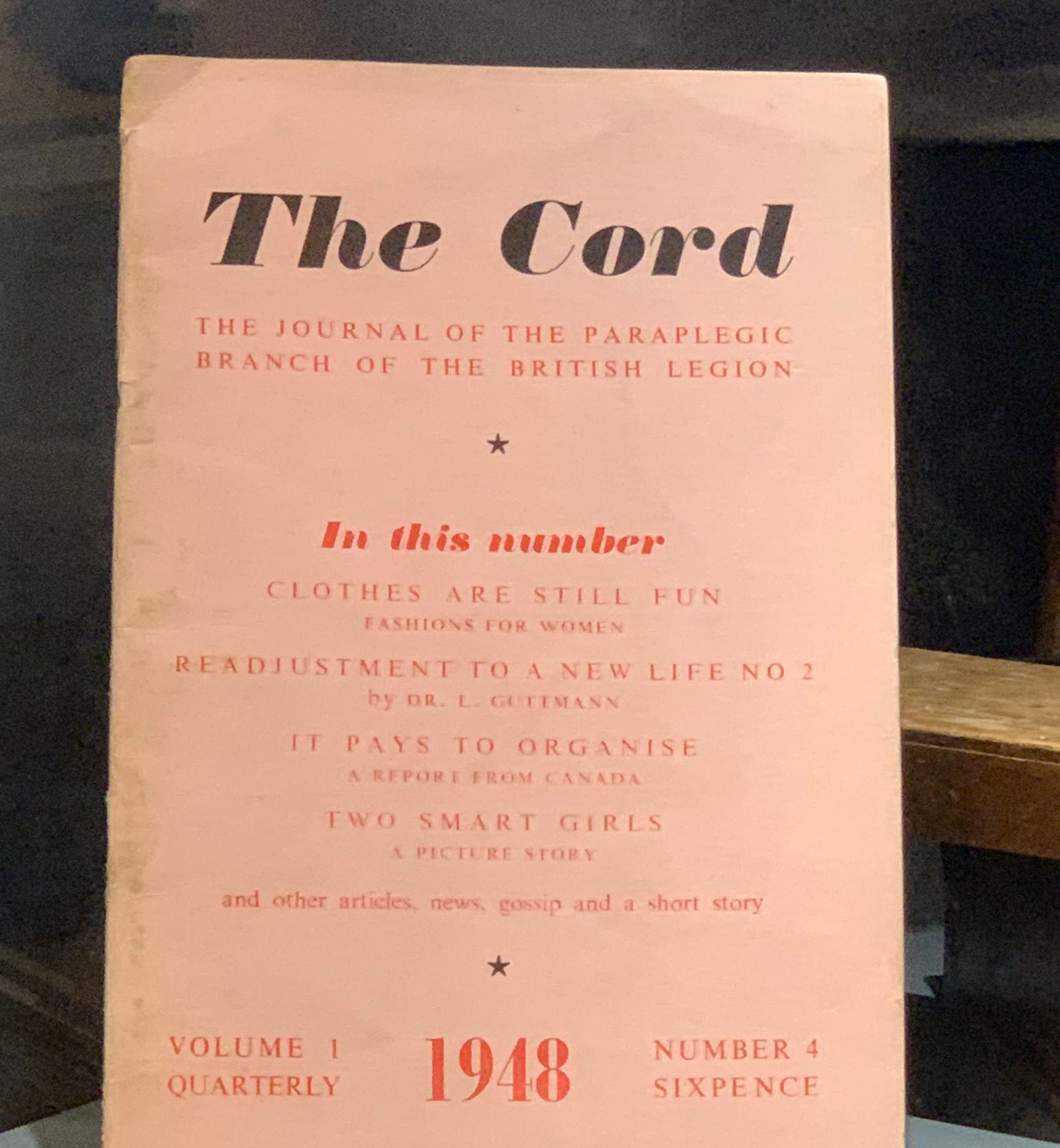

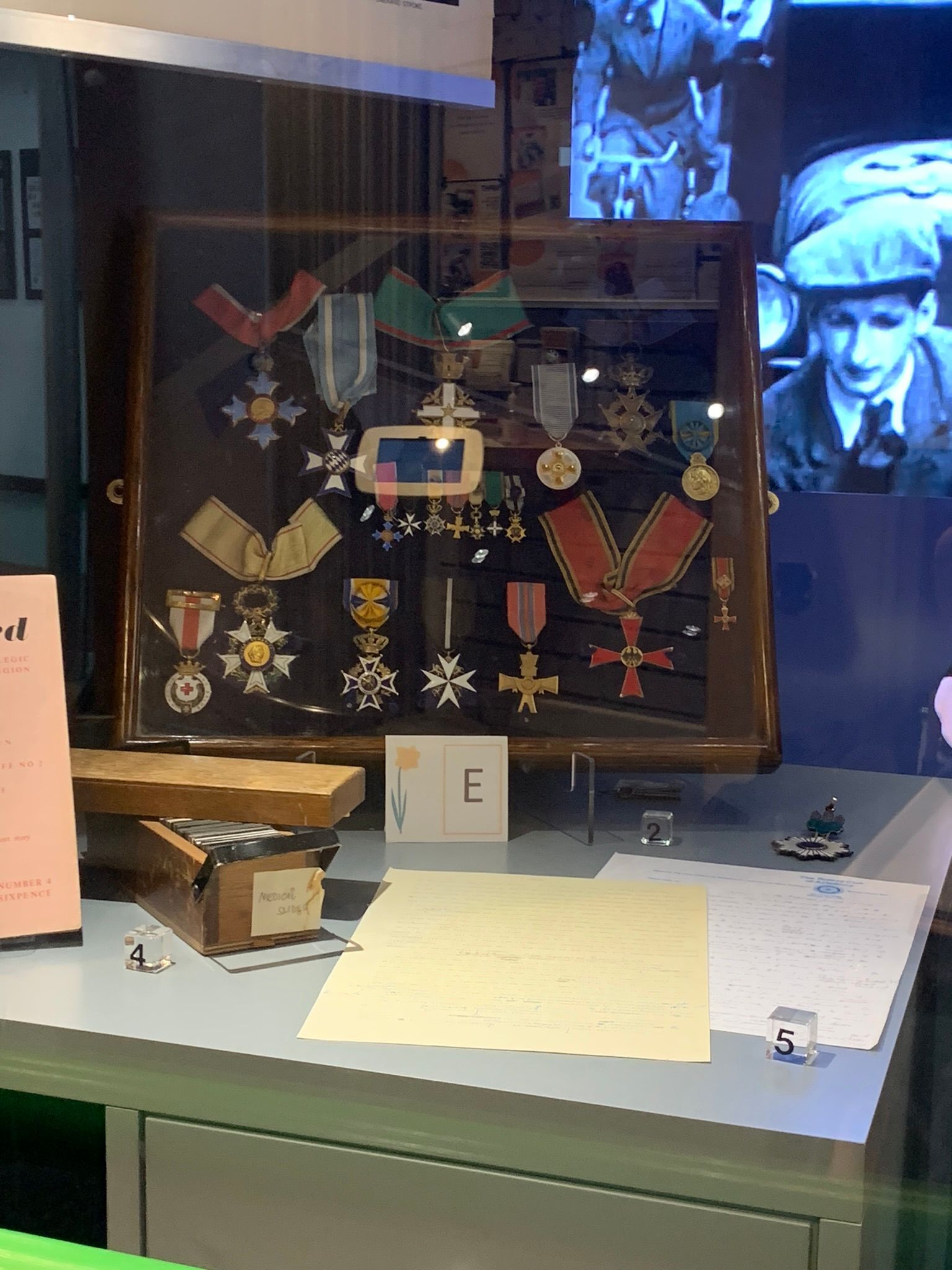

Walking to the left-hand side you are met with a portrait of the amazing Ludwig Guttman, followed by a case of artifacts including medals awarded to him during his life, medical slides, and a copy of ‘The Cord’ a magazine introduced by Guttman, produced and edited by the patients.

Slides from Ludwig Guttman used for International teaching

Button

A Magazine produced by SIr Ludwig Guttman and edited by patients

Button

Slide title

A Selection of medals awarded to Guttman over the years for his service and dedication to the centre and to the Spinal Injuries category.

Button

Slide title

The first gold medal awarded to Great Britain at the first offical Paralympic games in 1960

Button

Slide title

A bronze, silver, and gold medal from the 1984 Paralympics nicknamed the 'games of two cities'

Button

Slide title

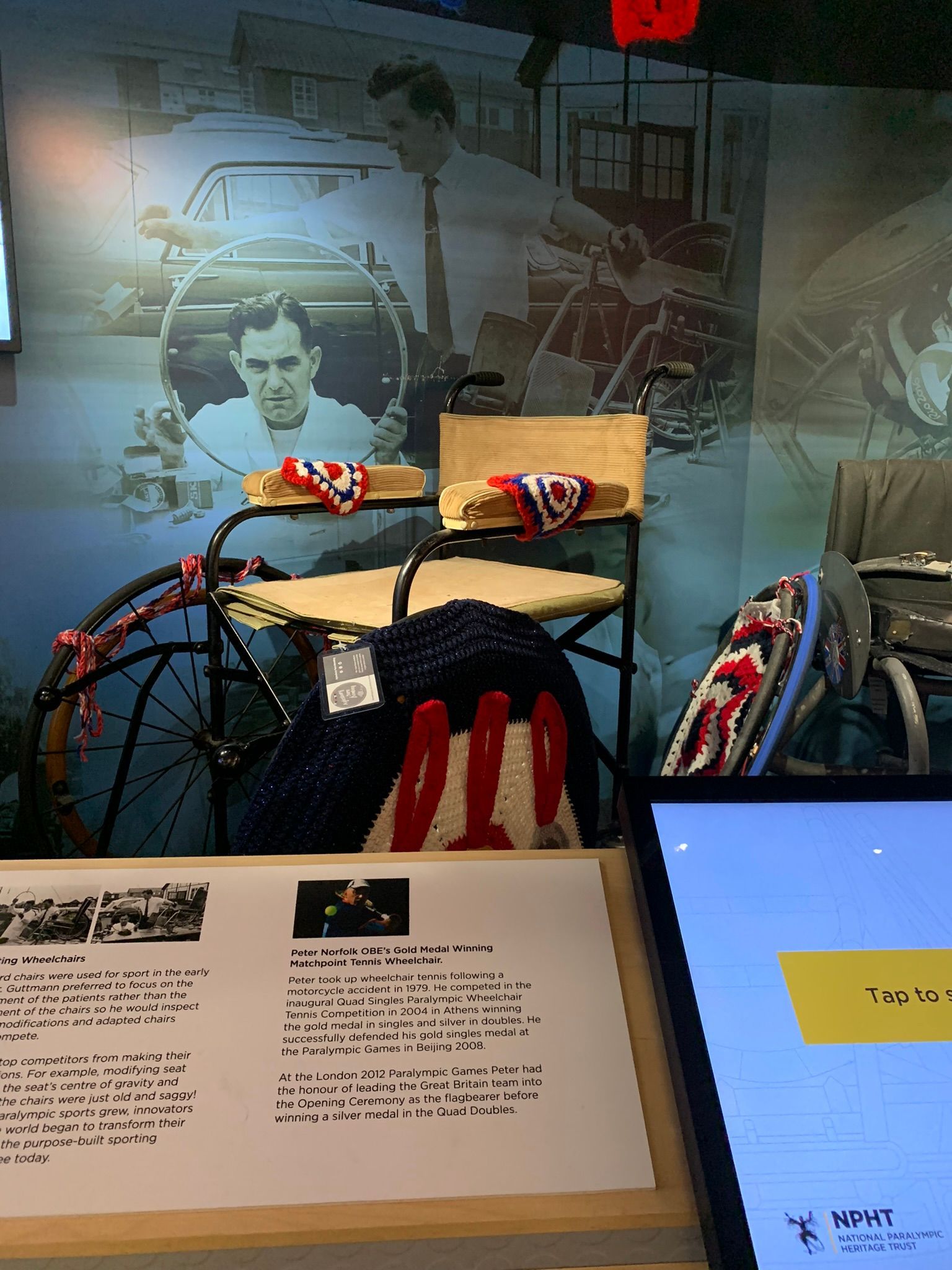

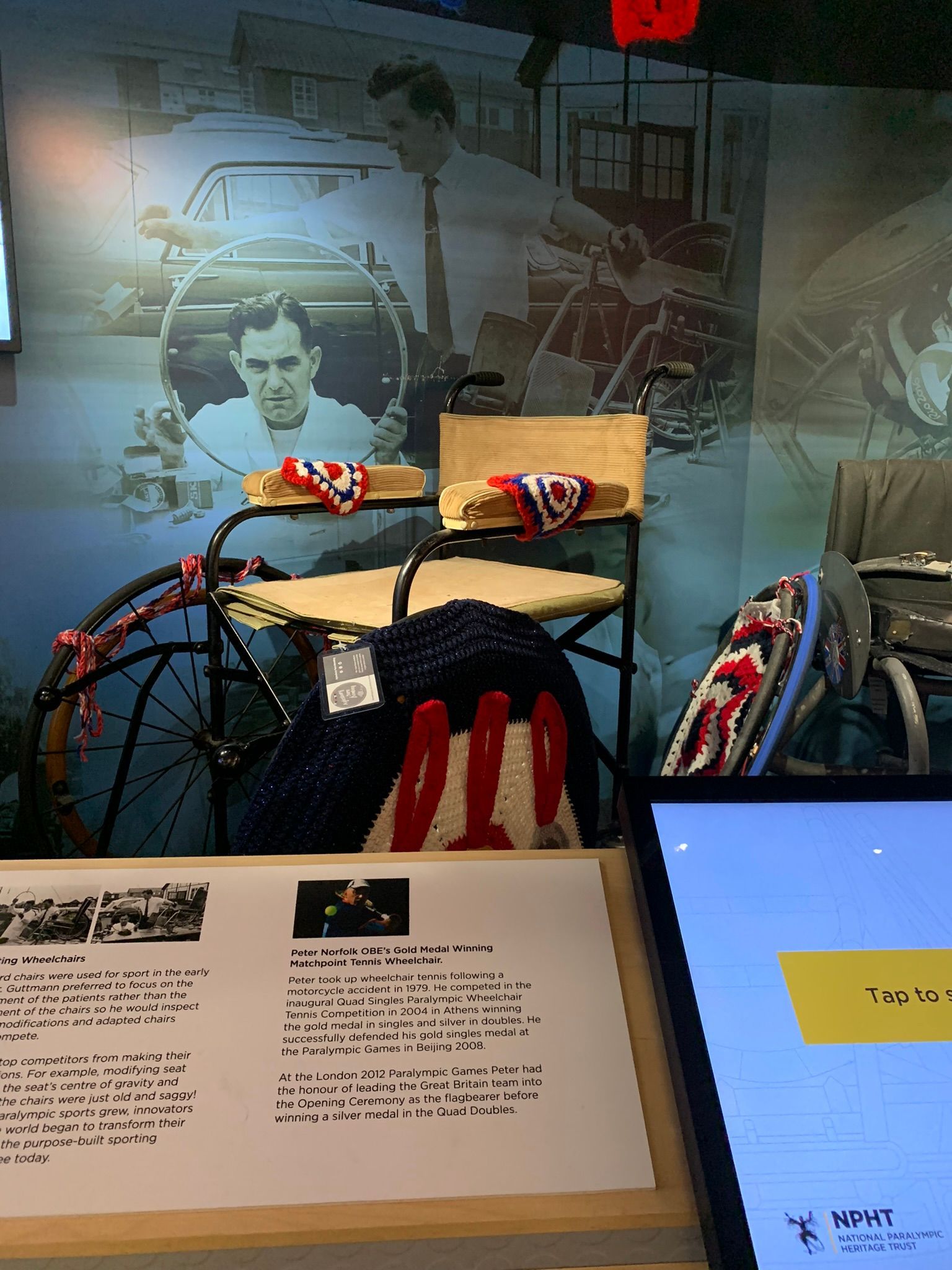

One of the first wheelchairs used for the games in 1948

Button

Slide title

The development of chairs for games to accomodate slanted wheels.

Button

Slide title

The Wheelchair used by Paul Cartwright in the 1984 Paralympics.

Button

Other memorabilia in the centre includes the first gold medal won by Great Britain in 1960 and a bronze, silver, and gold medal won at the ‘Games of two cities’ in 1984.

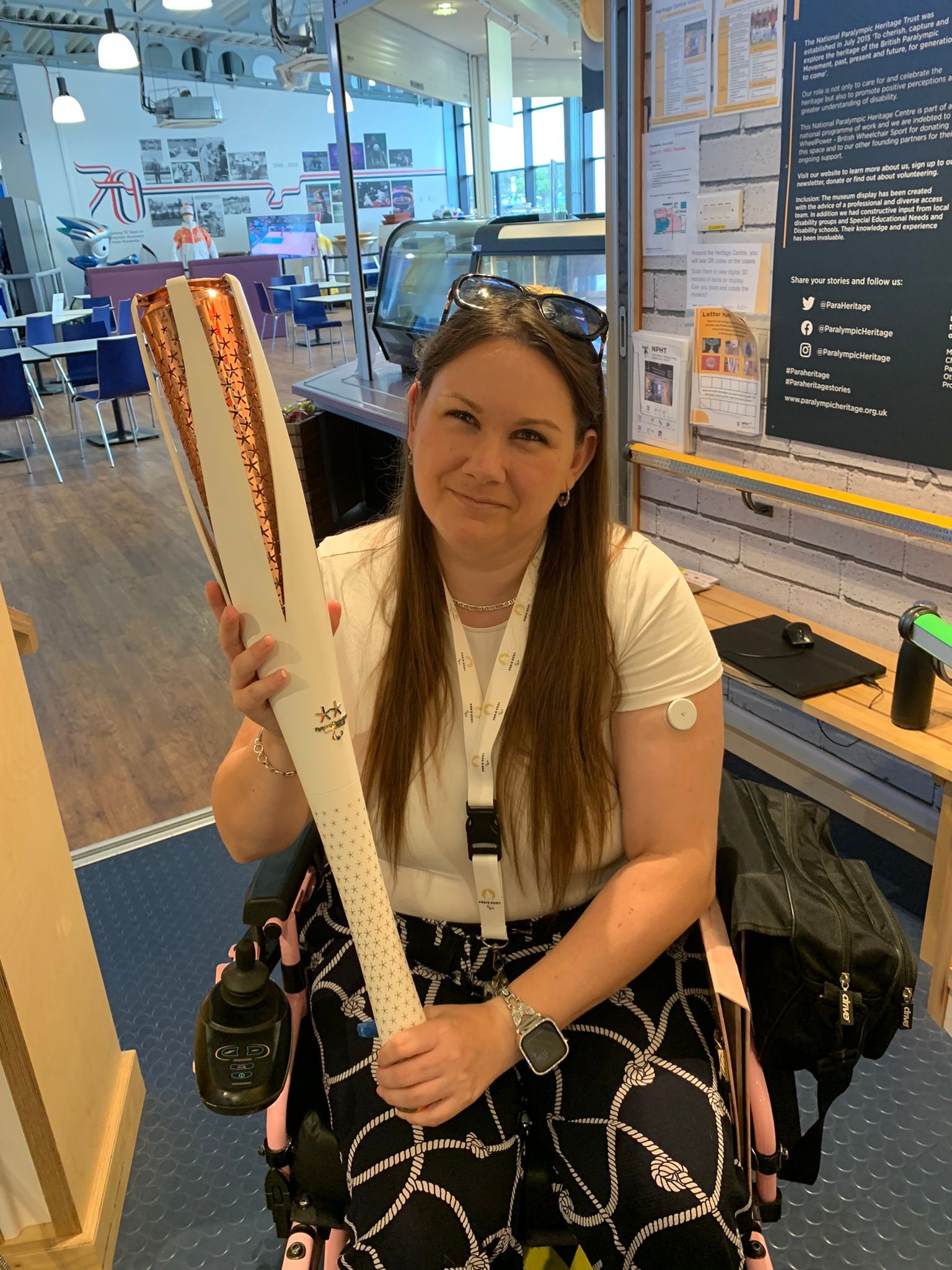

For myself, the most inspiring relic was the flame from London in 2012.

Missed by a few hours was the leg of ‘Last Leg’ host Adam Hills signed by the gold medallists of the Tokyo 2020 Paralympics, having just been packaged to ship to another location which will be going on a fundraising walk to help raise funds for the trust.

The boxes they have stored filled with treasures make you feel like a kid in a candy shop.

However, the team wants to make the history and all the artifacts that go with it as accessible as possible. That is why they are launching several online projects which people can access to learn more.

The first is the ‘Global Virtual Museum’ showcasing the history of the Paralympics through an ‘innovative virtual space where visitors worldwide can explore the history of the Paralympic games from its birthplace in Stoke Mandeville’

Find out about Ludwig Guttman's life in the Guttman room. The Japanese Room sponsored by Mitsubishi, tells the story of how Japan was involved in the early years of the Paralympics and how Dr Yutaka Nakamura pushed for disabled people of all abilities to join the Paralympics long before it happened.

The Global Virtual Museum is at the start of its journey and has been created by trainees at the centre with a range of diverse disabilities. With guided tours still to be added to this feature as well as other disability sports rooms, this has the potential to be a great asset to people around the world to learn about the Paralympics history.

The team has created many learning features for its website, to be used either at home, in a school setting, or on a self-guided tour of the centre.

Upcoming Events

They often host events, currently, there is a

Story of the Games exhibition at St James Market Pavilion in London. The 15th of August is Family Day, where you can try your hand at Boccia, get to hold a Paralympic Flame, and enjoy arts and crafts, all for free!

Vicky Hope-Walker CEO of the National Heritage said,

‘The history of the paralympic movement is one of incredible pioneers and stories of human endevour. We are proud to showcase this important national history in central London this Summer and hope that it is enlightening for all and might even inspire our next generations of Paralympians’

The team has thought of everything to make the experience of learning about the history of the Paralympic games as accessible as can be.

Their mission ‘We exist to enlighten and inspire future generations by celebrating, cherishing and bringing the Paralympic heritage and its stories of human endeavour to life’

‘We exist to enlighten and inspire future generations by celebrating,

cherishing and bringing the Paralympic heritage and its stories of human endeavour to life’

Entrance to the centre is free of charge and can be accessed from 9am to 7pm Monday – Friday and 9 am – 4pm Saturday & Sunday.

For schools, clubs, and societies, interactive tours can be arranged.

The team has thought of it all and continues to provide the Guttman theory throughout with breathing exercises on their website to help calm before your visit to arrange for sensory toys to be available when you arrive.

Guttman’s Legacy

Guttman died in 1980 at the age of 80 leaving behind a legacy for many a disabled person. He also left behind his daughter Eva Loeffler who carried on his vision and was appointed the mayor of the London 2012 Paralympic Games athlete’s village.

Ludwig Guttman, would often say to his patients, ‘I will make a taxpayer out of every one of you’, his mission for most worked and successfully over the past 64 years, Great Britain has won circa of 670 Gold medals.

‘I will make a taxpayer out of every one of you’.

The history of the Paralympics is just as important as the history of the Olympics. Furthermore, we live in the country of its birthplace, not many people can say that, so whether you live 10 miles from the National Paralympic Heritage Centre and visit in person or live 100 miles from the centre, and visit virtually, find out more about the Paralympic history and why it means so much for disabled people.

I would like to thank the National Paralympic Heritage Trust and all their collaborations for preserving Paralympic artifacts and to

Guttman, a true national icon, may his memory continue burning brightly.